Linking host personality and parasitic infection: a meta-analysis

Linking host personality and parasitic infection: a meta-analysis

Piscitelli, A. P.; Messina, S.; Wauters, L. A.; Santicchia, F.; Matthysen, E.; Leirs, H.; Vanden Broecke, B.

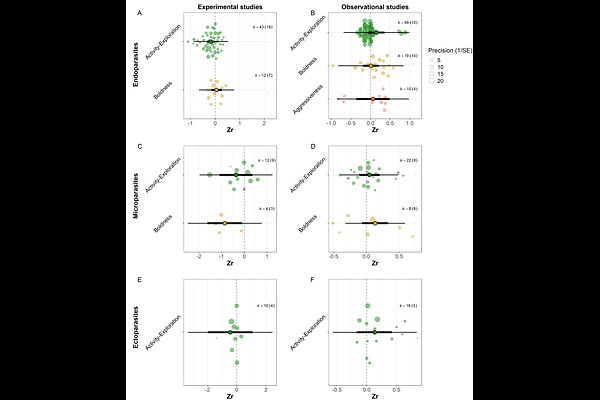

AbstractAnimal personality and parasite infections are key forces shaping the ecology and evolution of natural populations. Personality traits, such as activity, exploration, and boldness, shape how individuals interact with their environment and conspecifics, influencing both their exposure and susceptibility to parasite infection. In turn, parasites can impact host fitness and energy allocation, and may modify host behaviour either through manipulations to enhance transmission or as consequences of energetic trade-offs associated with mounting an immune response. Despite growing interest in the interplay between behaviour and infection, the overall directionality and consistency of personality-parasite relationships remain unclear. This relationship is further modulated by ecological and biological factors, such as parasite type (e.g. micro-, ecto-, or endoparasites) and host type (e.g. intermediate versus definitive), which can influence both infection risk and the nature of behavioural responses. To disentangle these effects, we performed a meta-analysis of 226 effect sizes across 80 studies, assessing (i) the impact of experimental infections on host personality traits, and (ii) the correlation between personality and infection status in observational studies of wild populations, while accounting for variation in parasite groups and host roles. In experimental studies, infected hosts exhibited significantly reduced levels of activity and exploration, while effects on boldness and aggressiveness were non-significant. These findings suggest that infection imposes energetic costs that suppress behaviours requiring sustained effort, such as movement and exploration. Conversely, observational studies showed a positive association between activity-exploration and infection probability, likely reflecting greater exposure of more active individuals to parasites via increased interaction with conspecifics or contaminated environments. Meta-regression analyses further revealed that parasite type and host role modulate personality-infection dynamics. In experimental studies, microparasites were associated with reduced boldness and activity-exploration, while endoparasites led to reduced activity-exploration, particularly in intermediate hosts. Notably, hosts showed significant behavioural suppression in experimental contexts, but not in observational studies, potentially indicating that behaviourally tolerant individuals are favoured in natural environments where personality traits relate directly to fitness. Together, these findings underscore the importance of ecological context and study design in interpreting personality-parasite associations. Experimental infections tend to reveal the physiological costs of infection, while observational studies highlight behavioural traits that modulate infection risk. By integrating data across host types, parasite groups, and methodological approaches, our meta-analysis provides a more comprehensive understanding of how personality and infection interact. These insights contribute to a broader effort to link behavioural ecology with disease ecology, clarifying how individual variation in behaviour shapes and is shaped by host-parasite dynamics.